Manage Your Data

Many of us use digital platforms, such as Spotify, Google, or Goodreads, without realizing we have a right to access the data that we generate on them. We cede certain elements of privacy when we register for and upload content to fitness apps and other like-minded interfaces. Yes, we get the benefit of community and easy access to our metrics, but we also give companies our data for free and trust that they will be good stewards of it. Most of these interfaces do have APIs or tools that allow us to extract the data that ends up there; see Spotify’s, for example. Strava, which hosts the burgeoning PhDistance group (see below for instructions on how to join), also has an API with instructions on returning many elements of one’s workout data. These are valuable tools.

In most cases, out-of-the box interfaces themselves are sufficient for understanding locational and biometric data associated with running. Some people pay a premium rate to access fancy heat maps and other features, but even in these scenarios, one is beholden to the views and metrics that the system provides. There is an upside to establishing a workflow for downloading and managing the data you generate that does not lock you into a single platform.

Owning your data takes a lot of work, and even people who are vested in data management for a living often don’t take the steps required to manage data actively. By “owning your data,” I mean downloading the actual data files, keeping them in a storage location that you control, converting them to more useful, interoperable and persistent formats, and generally organizing them in a way that better makes sense to you. In this instance, the data in question is a .gpx (Geospatial Exchange Format), an open, lightweight file format that has been around since the early 2000s. Every time you record an activity with a GPS device, such as a phone or a watch, one of these files is generated.

Why do download your data files? There are many potential reasons, the most compelling of which is the potential to ask questions that are unique to your own experience as a runner. As a caveat, though, I have to admit that I don’t always follow my own advice in storing and managing data. It’s a well-known trope among librarians. Nevertheless, here’s a few reasons why it’s a good idea:

-

Keeping your data organized liberates you from being locked into a single app or product. If you’re interested in tracking your progress over a timespan that could include many years, keeping your data as portable as possible helps. For example, you may have run with a Garmin for 5 years and then decide to switch to a different device or a different brand, such as a Coros. When your files are downloaded, you can port in historical running data, or augment data with metrics provided by a new system.

-

Having access to your data will allow you to visualize and perform analysis that makes sense to you. By using free and open source software (FOSS) like QGIS, Python and its many visualization libraries, or R and its robust analysis tools, you can ask more flexible, capacious questions about your running than what is offered in many fitness apps by default. Doing this takes a lot of data and software prowess, but it can also be a lot of fun.

-

If you want to maintain a more granular approach to sharing data to the world, you can practice offline analysis and not worry about other people seeing warm-up runs, recovery runs, or other workouts that don’t represent what you’d like.

-

Having portable data affords you the ability to enrich your data with many other kinds of indicators. For example, have you ever wondered whether your overall running performance varies in zip codes that are one standard deviation above or below the national poverty line?

A Simple Example

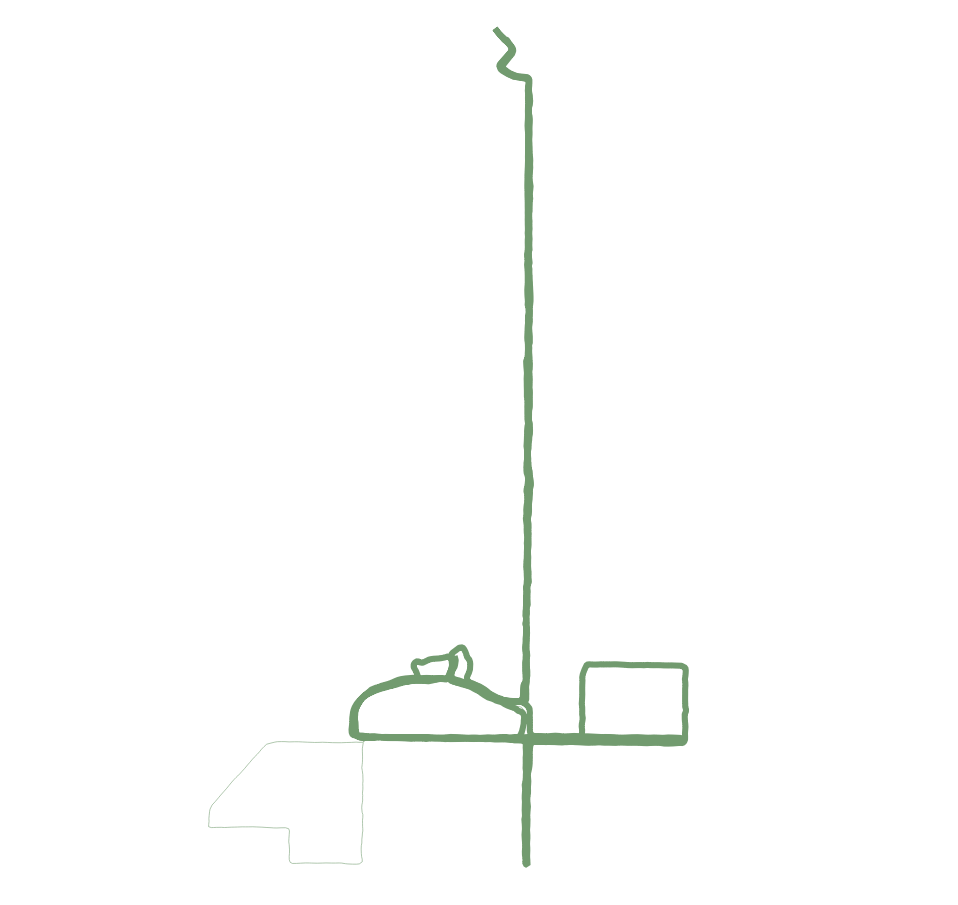

A couple weeks ago, I went on a trip. For the sake of demonstration, let’s say I download the .gpx files for the four runs I did while I was visiting. Once I downloaded the files, I used QGIS to build a map in which my runs are visualized as a line whose thickness varies according to my maximum heart rate during that run.

This is very specific, and I am keeping the data relatively devoid of context here so as to not reveal my exact location. However, it’s an example of how I can make a visualization that is based in a single question: where do I run when I am pushing myself the hardest, where hardest is expressed by maximum heart rate?

Here’s how I did it, in broad strokes:

- I downloaded all of my .gpx files from my Garmin account

- I used QGIS to import each of the .gpx files I had downloaded as vector layers

- I used the Merge Vector Layers tool to combine the polyline features into a Shapefile. Doing this allows me to take a single file with many runs on it and bring it into any other GIS analysis or visualization platform I’d like later on

- Because each run needs a unique identifier, I used the Field Calculator tool to strip out the run ID into its own column

- I then went back to Garmin and exported the “metrics” data as a .csv

- I merged it in QGIS, and then stylized the run according to my maximum heart rate.

I agree that knowing how to do all of these things presupposed a lot of already-existing knowledge with QGIS, and I don’t think it’s the focus of this newsletter to go through those steps one by one. At least not yet. But I leave it here as a provocation, and I hope it will inspire others to practice good data management and pose similar questions. It’s the foundation for many other fun visualization styles to come.

Other Quick Hits

This week I’m heading into the final tune-up run for the 2022 United Airlines NYC Half Marathon. I’ve written about this race previously, and it remains one of my favorites. I’ve been feeling good and am hoping for another perfect weather day.

PhDistance is on Instagram and Strava

If you like reading what we’ve come up with so far in the newsletter, you might also want to connect with PhDistance on two of the leading social media platforms out there today: Instagram and Strava. That’s right! We’ve created an Instagram feed at phdistancerunning and a Strava club.

How do I subscribe?

If you want to receive our newsletters or rifle through the long lost archives of previous posts, just enter your e mail address on this form. You will get copies of the newsletter sent to your email. That’s it.

See this newsletter online

Newsletter 20: “Manage Your Data”