Ignore the Message

Anyone who decides to run with a fitness tracking device or GPS watch knows that the experience can be a double-eged sword. On the one hand, devices can provide the context and data to help take your running and fitness to the next level, if that’s what you’re seeking. Especially if you use data for post hoc analysis like monitoring your cadence, to use one example, you can begin to grow physically and mentally. Aside from helping measure your pace, elevation climb, and other physiological registers (such as heart rate), watch data can ground you in a process and allow running that has necessarily been independent and private to become a communal practice, as the recent proliferation of virtual races demonstrates.

However, there are some drawbacks to the ways that our fitness tracking devices communicate to us. It can become problematic if we fixate on the in-the-moment feedback from our devices while we run. It’s almost always better to head out and naturally settle into a pace, check in with our breathing and with our muscles or flexibility, and just enjoy the experience for what it is while we’re out there.

It can also become a problem if we fixate on the feedback after our workout is over. Some of the more popular app interfaces, like Garmin Connect and Strava, allow us to upload the data from our runs, and they display it in a dashboard portfolio with contextual messages that may not be accurate. Worse, these messages and cues have the potential to make us feel artificially confident about our runs or, unnecessarily bad about the efforts we did put in.

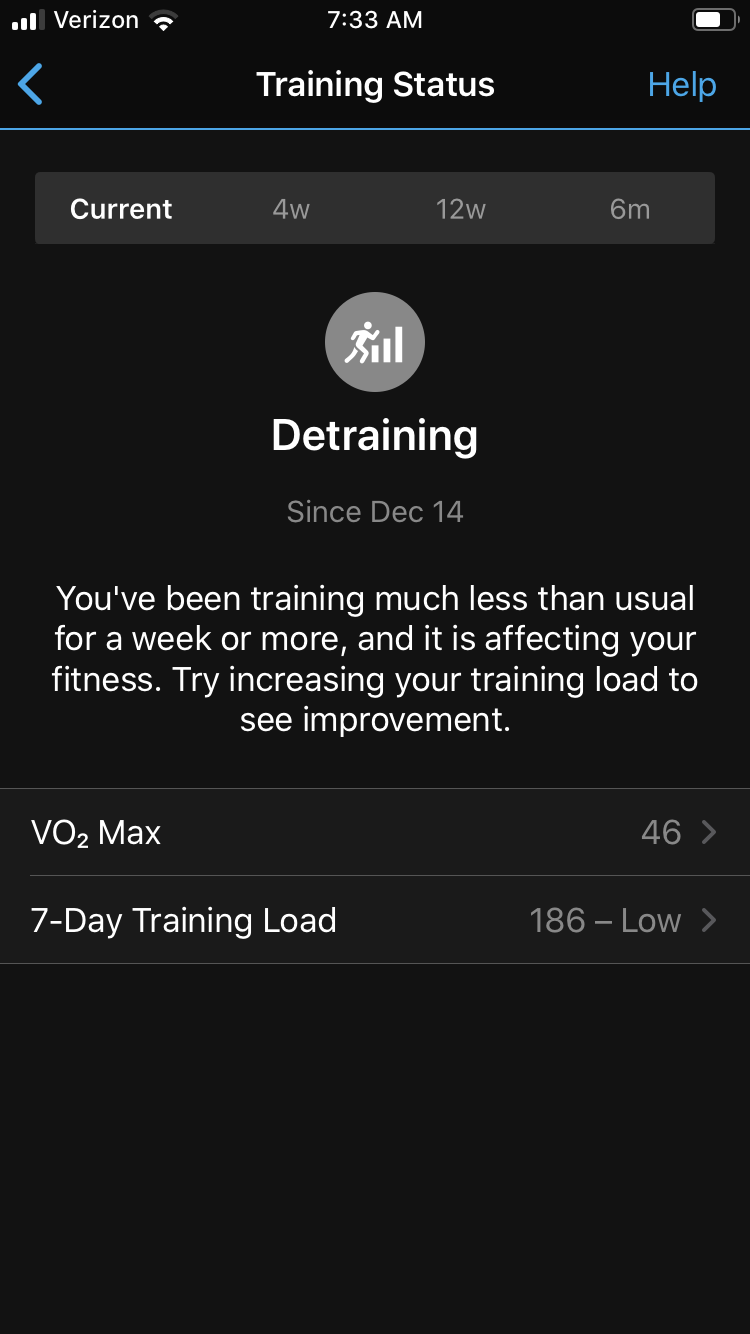

Those who use running devices regularly know what I’m talking about. When I finish a run, my Garmin watch tells me how many hours I should spend recovering. It also tracks some derived fitness metrics, such as Training Status, and returns a label for that run, such as Productive or Unproductive. In many cases, I am surprised when I read these statuses, and I have become increasingly frustrated with the way they make me feel about my running experiences.

I recently went on a short run that felt okay. I was intentionally going a bit slower than normal, but I had dressed with a bit too many layers. When I got back, Garmin said that my Training Status was “Unproductive,” likely because it sensed a relative disparity between my heart rate and the speed I ran. Strava can send similar messages to us, like “this run was harder than normal,” and it even offers comparative analytics to track against “matched runs.” In other examples, the messaging comes in the form of online training programs, which set a rigid schedule and throw us green checks for meeting a weekly distance threshold or red checks for missing a running workout. The reality is that training cycles are rarely so definitive.

What’s really going on here?

In this post, I am dancing around a few important things related to fitness data, and data in general, and I hope to take up some of them in future newsletters. But for now, let’s think about what’s actually going on with the fitness messaging in our apps.

- Fitness applications are, at base, just that: applications that are designed to be literal representations of input data.

- Fitness applications are not sophisticated enough to be aware of the many contextual elements that surround our runs. They don’t know whether or not we are running with a friend who goes more slowly than we normally run or (conversely) pushes us beyond our comfort zone.

- A lot of the labels that are generated are the byproduct of complicated, proprietary estimation methods. In the case of Garmin, the messages are derived from the FirstBeat Technologies Ltd. VO2 max estimation algorithm, which pulls in data points from heart rate and speed. Not only might these be inaccurate, but they also are limited to the set of data that exists within a user account already.

How the messing can go wrong

Here’s another example of why we really need to rely on more than just running data to frame our experiences and sense of accomplishment. This past summer I was in the throes of recovering from an injury, and I was instructed to do some interval running and focus on increasing my cadence. Because I was taking a running approach that was not reflective of the way I normally run, specifically one in which my heart rate would recover in between high-cadence intervals of running, Garmin started to interpret the results as an overall increase in fitness my level and an overall spike in my V02 max, or the amount of oxygen one’s body can absorb during exercise.

In fact neither increase was really true, so as I slowly began to heal and return to longer intervals, the messages after my runs cut even more deeply. Just when I felt that I was making progress, Garmin was telling me that my fitness level was decreasing that that I was “overreaching.” This is just one example, but there are probably many others. It’s hard for our watches to account for temperature and humidity fluctuations. Our emotions can artificially influence heart rate data. We might be breaking in a new pair of shoes. We could be running with a backpack full of clothes. Variance is the result of many factors.

Learn to ignore the noise

I anticipate that metrics is a general topic I will return to in the newsletter periodically. But for now, just remember that there are different kinds of running, different goals, and different occasions, and if we are going to take cues from the feedback that data and fitness apps give us, we need to learn how to look at the entire process flexibly.

Resolution for the 2020 New York City marathon

This week the New York Road Runners announced that those who had registered for the 2020 NYC Marathon can now rank order their top two preferences regarding running the race in the future: run in 2021, run in 2022, run in 2023, or receive a refund. I am hoping for a spot in the 2021 race, so we will see what happens. In general though, this seems like a reasonable way to move forward and account for the lost year of racing. I am interested, in general, in the topic of how races across the U.S. will begin to handle make-ups and offer resolutions as we slowly emerge from a global pandemic.

How do I subscribe?

If you want to receive our newsletters, just enter your e mail address on this form. You will get copies of the newsletter sent to your email. That’s it.

See this newsletter online

- Newsletter 7: “Ignore the Message”

- All prior PhDistance newsletters